b.1881-1915

1880s – Alfred’s birth in the East End and his father’s work.

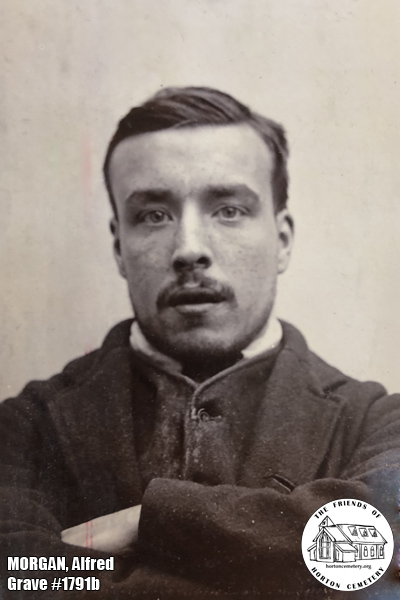

In May of 1881, the walls of 5 Buttesland Street in Hoxton, London resounded to the cries of a baby, Alfred Samuel Morgan. Alfred was born the sixth of seven children to Henry and Emma Morgan, a working-class family with a sizable home. It was opposite Aske Gardens- formerly the Aske hospital – the oldest and most grand alms-house in the Shoreditch area.

Shoreditch was a bustling place of industry and commerce, and with that came cheap labour. Social reformer Charles Booth commented ‘The character of the whole locality is working-class. Poverty is everywhere, with a considerable admixture of the very poor and vicious… Hoxton is known for its coasters and curtain criminals, for its furniture trade.’ (Life and Labour of the People in London,1902.)

Alfred’s father, Henry worked as a cabinet maker, later specialising in the craft of portmanteau. This profession, according to Booth’s poverty map, would have afforded the family up to 30 shillings per year. Like many tradesmen, it was often customary for children to follow in their father’s footsteps and learn the family trade. Whilst Alfred’s siblings went on to become warehousemen, black saddle makers and coach trimming makers, Alfred had a tragic and short-lived life as we will discover.

1890s – Tragedy for the Morgan family

In 1891, the year most remembered for great blizzards that consumed the south of England, the Morgan family had relocated just down the street to number 63, and the house would have been a bustling hive of activity. With 5 older siblings, Alfred would have been surrounded with the comings and goings of a hectic family life.

When he was seven years old, Alfred would cease to be the youngest of the Morgan clan. A little sister, Florence was born in 1889 and completed the family, stretching space in number 63 that little but further. This is the last time we see the Morgan family living under one roof.

A shocking turn would have enormous consequences for the entire family. Sadly, in November 1893, Henry Morgan passed away at just 49, with no records indicating the cause of his death. We can see that he left the effects of £128 to support his family which according to the National Archives would be estimated at £10,500 in 2017.

Losing a parent would have shaken the Morgan family to the core. With the main source of income no longer present, the older children would have had to come together to help provide for the younger. Alfred was just 12 years old when he lost his father, which would have had a profound effect on him.

More Tragedy

Tragically this was not the end of heartbreak for the Morgan family, when just three months later the children’s mother Emma passed away aged 46, leaving all five children orphans. The eldest would have been able to seek out their own lives, but for the three youngest children in their early teens, life would have been difficult.

We know during this time, contagious diseases were rife through London, and more specifically in Shoreditch which could have been one of many reasons why the parents were taken so quickly.

Alfred was just 13 years old when he was orphaned, however, there are no documents to indicate his whereabouts after his parent’s death. 63 Buttesman Street, which was once filled with laughter and the charms of close family life, was now empty.

1900s – Alone in the Workhouse

The next time we see Alfred is in the 1901 census, where he is a patient at Shoreditch Infirmary at St Leonards Workhouse. Within the seven years that Alfred goes missing in our paper trail, his life had dramatically turned upside down and he ended up in the workhouse as a pauper, serving in the infirmary. Whilst Alfred battled with his medical and economic conditions, older siblings, Henry, Frederick, Elizabeth, Edward and Rosa were all settled elsewhere and working. Younger sister Florence was living in Reedham Asylum, later renamed Reedham Orphanage. Florence was just six when both her parents had died, and it was clear her siblings were in no position to care for her.

From the array of documents in the ‘Selected Poor Law and Removal Settlement Records, 1698-1930’, we begin to see the state of Alfred’s condition. Between 31st May and 2nd June 1902, Alfred was in the Workhouse and was admitted to the asylum in St Leonards, Shoreditch.

Alfred’s medical record

From Alfred’s statement of peculiars, we have a glimpse of his struggle with illness. The record states that Alfred had suffered a mental ‘attack’ of some kind, which had lasted for two weeks with the supposed cause being epilepsy. Whilst of course these were just health officers’ first assumptions, it was clear that Alfred was very poorly. Alfred was suffering with ‘the perversions of lunacy,’ according to R.W Partridge, Asylums Clerk.

Weighing 11st and 5lb, Alfred was in a desperate state upon his entry into the asylum. He had clearly battled with his condition previously. Alfred had several scars on the back of his head – an educated assumption could suggest they were from the effects of epileptic fits. His face was covered in acne – a boy forced into the role of a man at a premature age. The medical practitioner’s notes at the time state that Alfred was ‘vacant’, his memory was bad and he would walk around aimlessly whilst looking at people frightened and ‘wildly’.

After having lost his parents as well as all contact with his siblings, battling the severe effects of epilepsy, it was clear life had taken a toll on Alfred. As his condition progressed, his doctors noted him as being violent, morose, incoherent and having a defective memory. It was clear Alfred was very sick during his stay at Hanwell, with his mental state only appearing to be deteriorating.

We learn about Alfred from others

Perhaps what makes it even more tragic, is the observations of Alfred through his peers and neighbours. James Grant, an attendant for Shoreditch infirmary, stated that before admittance into Hanwell, Alfred was in fact violent at times and had to be placed in the padded room. James also reaffirmed previous observations of Alfred that he would walk around aimlessly unaware of what he was doing.

Other inmates related that Alfred was noisy, aggressive, and perhaps most unusually, ‘useless.’ Alfred had told staff that he believed electricity was being put ‘in’ him, perhaps it was the only way his mind could process the horror of his situation.

Shockingly Alfred was “Discharged Relieved” from Hanwell Asylum on 30/10/1903. Until further records are found we do not know where Alfred went on his discharge and we do not know what happened next in Alfred’s story.

We do know that he spent time, but as yet not how long, in St Ebba’s epileptic colony in Epsom (also called Epsom Colony, Ewell Colony and The Colony) before passing away in May 1915.

Hopefully we can find his admission records to this hospital and they will give us more information. Currently the UK Lunacy Register records up to 1912 have been digitised and are available on ANCESTRY.COM. The remaining records are in the UK National Archive in Kew. We may be able to find Alfred’s admission to St. Ebba’s there or, at the Surrey History Centre.

Author’s thoughts

The collection of documents relating to Alfred are certainly a heart-breaking read, a victim of misunderstanding doctors, low income and severe bad luck. This left Alfred on a path he could not escape. Losing his parents at an early age and suffering a health condition that doctors at the time simply did not understand left Alfred in a vulnerable position.