b.1857-d.1910

Introduction

Tracing Emily back in time from her death in 1910 reveals that she was institutionalised from as early as 1881, when she would have been no more than about 24 years old. Definitively finding her before that point has proved challenging. What took her to the first asylum also remains unknown. For that reason, this story initially begins in 1881.

1881

Emily first appears in the Lunacy Patient Registers on October 7th 1881, when she is admitted to the Kent County Lunatic Asylum which was in Maidstone. There is no evidence as to why she was admitted.

Her life just prior to entry is a mystery. There is an Emily Hillier of the right age working as a servant in Kensington, but there is no solid evidence that this is her. If it is her, perhaps something happened that led to her being admitted to an asylum. We know that sometimes young women fell pregnant and were admitted to asylums but this is just speculation in the absence of other evidence. The date of the Census in 1881 was April 3rd, so this is possibly her.

From this point, Emily does not leave institutions until she dies in 1910. Each record meticulously links the date she leaves one asylum and enters another. Research for other stories for this project has shown that people were moved all over the place, sometimes great distances. Were they moved for treatments? Was it an issue of overcrowding?

Emily’s journey

October 7th 1881, she enters Kent Asylum, in Maidstone, patient number 78717.

She is transferred to Banstead on June 12th 1882.

She is transferred to Exeter on March 17th 1890.

She is transferred back to Banstead on November 6th 1894.

On August 27th 1897, Emily is discharged from Banstead and is admitted to Fisherton in Salisbury.

By September 8th 1899, she is returned to Banstead.

She is transferred to Leicester on September 26th 1901 and leaves there a year or so later, on November 15th 1902, when she goes to Epsom, to the Horton Asylum.

On May 14th 1906, after a fairly stable period of time, Emily leaves Horton and is admitted to Fisherton again.

Finally, her journey ends when she is discharged from Fisherton on July 11th 1907 and is admitted to Long Grove in Epsom.

Emily dies at Long Grove on April 5th 1910 and is buried in the Horton Cemetery.

Her story is like so many others, quite tragic. There is a sense of torment about it, with so much disruption, travel and new locations. Surely that would have caused a patient trauma and upset. There is something strangely comforting that she finally stopped and found peace.

Prior to 1881

But what of Emily’s earlier life? There are a couple of possibilities for Emily’s family in the records, neither definitively proven. However, one particular family has regular visits to the workhouse in the early 1860s and it is this one which might be a likely candidate.

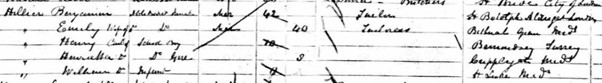

This Emily was born June 15th 1855 and was baptised at St Giles without Cripplegate, London on May 23rd 1855. Her father, Henry Benjamin Hillier was a tailor, born in 1818. He had married Emily’s mother, also called Emily on June 21st 1842 at St Andrew’s Church, Holborn.

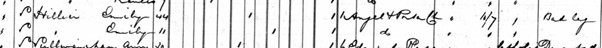

By as early as February 23rd 1861, Emily aged 5 years, has been admitted to the workhouse with her mother and siblings (Henry aged 9, Henrietta aged 7, and William aged 6 days). Emily senior was in labour when admitted. Benjamin, the father, is not present but appears to join them later because on April 19th 1861, the whole family leaves the workhouse. They must have fallen on hard times.

In the Census return for 1861, Benjamin, Emily and the family, including the new born William are listed as inmates at an unknown institution. Strangely Emily, the child, is not with them.

Sadly, on October 3rd 1861, the new-born William dies.

On February 7th 1862, mother Emily and three children (including an Amelia) enter the workhouse again but not Emily, the child, or her father. I might guess that Emily was written incorrectly and this is in fact Emily because the age is about right. The record indicates that they are destitute. Henrietta and ‘Amelia’/Emily are discharged on February 13th 1862.

Then later on in July 1866, just Emily and her mother enter the workhouse. The record indicates that her mother has a bad leg, which suggests that entering the workhouse provided medical treatment.

Life in the workhouse

For many, the word ‘workhouse’ conjures up the image of an orphaned Oliver Twist begging for food from a cruel master. The reality, however, was somewhat different, and Britain’s system of poor relief arguably saved thousands of people from starvation.

The Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834, meant that workhouses were now administered by unions – groupings of parishes – presided over by a locally elected Board of Guardians. Each union was responsible for providing a central workhouse for its member parishes, and out relief was abolished except in special cases. For the able-bodied poor, it was the workhouse or nothing.

“Entering the workhouse was not simply a matter of turning up at the gate,” says Peter Higginbotham, author of The Workhouse Cookbook. “The poor would first meet with a relieving officer who toured the union on a regular basis. In most cases they would be ‘offered the house’ and given a ticket of admission. The family would then make its way to the workhouse, where their clothes were put into storage, and they would be issued with a uniform, given a bath and subjected to a medical examination.”

Men and women were separated, as were the able-bodied and infirm. Those who were able to work did so for their bed and board. Women took on domestic chores such as cooking, laundry and sewing, while men performed physical labour, usually stone breaking, oakum picking or bone crushing. Conditions were basic: parents and children were permitted to meet briefly on a daily basis, or on Sundays. Inmates ate simple fare in a large communal dining hall, and were compelled to take regular, supervised baths.

After 1866, there is no evidence found so far to place Emily in any institution until 1881. There is however, evidence that the sister Henrietta continues to go in and out of the workhouse and the asylum.

Whilst it is not definite that this is Emily’s family, the evidence of workhouse and asylum entries suggests that perhaps this is the right choice. No other Emily Hillier appears to be in the records.

Author’s thoughts

Yet another ordinary person with an ordinary life structured by life in institutions. How different Emily’s life might have been, had she had care and support as she might be entitled to today.