b.1861-d.1915.

Elizabeth’s parents and siblings

Elizabeth Coombes was born Elizabeth Eltringham on 10 July 1861 to parents, Alexander Eltringham (1829-1876) and Elizabeth Holmes (1830-1898), who married on 19th June 1848 at St Andrews Church, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Northumberland.

Altogether I have found the births of eight children but two were lost in their first year, Elizabeth born1852 and Alexander born 1859.

Their surviving children were Eleanor (Ellen) born 1848, Ralph born 1849, Elizabeth born 1852, Jane born 1856, Alexander born 1859, Elizabeth born 1861, Alexander born 1864 and Hannah born 1868.

Alexander’s parents were Ralph Eltringham and Ann Graham both born 1803 in Gateshead. They married in Newcastle on 30 June 1825. Ralph was a steel worker. Elizabeth’s parents were Samuel and Ann Holmes. Unfortunately Samuel appears to have died in 1835 when Elizabeth was just 12 years old.

The Eltringham family lived all their lives in Gateshead, initially in “Blackwall,” and then, in the 1861 Census, the family is shown living at 13, Clavering Street, Gateshead, Alexander’s occupation is given as “iron roller” and Elenor, Ralph, Ann and Jane are noted. Later that year Elizabeth was born. She was baptised on 29th July 1861 in Gateshead.

The 1871 Census gives the family address as 47, Berwick Street, Gateshead, and Elizabeth , Alexander and Hannah are shown. The family is complete.

Sadly Elizabeth’s father Alexander died in late September 1876; he was buried in Gateshead Parish on 1st Oct 1876.

Elizabeth works as a domestic servant

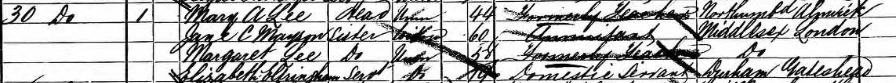

By 1881 Elizabeth is 19 years old and we find her living and working as a domestic servant for three elderly sisters at 30, Simpson Street, Newcastle on Tyne. Two of the sisters were former teachers and the third is a widow so we can hope that this was a good situation for Elizabeth.

Elizabeth marries and moves to Greenwich

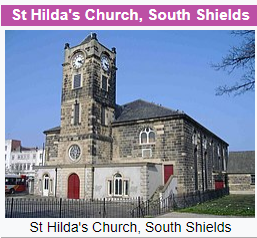

On 14 August 1883 Elizabeth married James Peter Coombes /Coombs (1862 – 1907) at St Hilda’s Church, South Shields, situated in the market square.

Postcard sent 1904.

Her birth year is given as 1864, aged 19 years, and her father is shown as John Eltringham. Her wedding took place after her father’s death so we can assume that John was possibly and uncle or cousin.

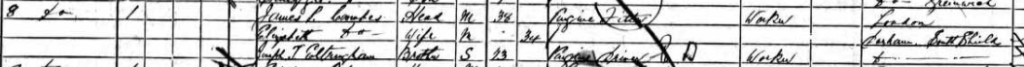

The only census found for James and Elizabeth after their marriage is in 1901 when they were living at 8, River Terrace, Greenwich. James says he is born in London in 1863 and that he is an “engine fitter.” Living with them is Joseph T Eltringham born 1878 in South Shields. His occupation is given as “engine driver.” Joseph is said to be single and a ‘brother’.

In the visitors’ book for the Manor Asylum Joseph T Eltringham appears again as Elizabeth’s brother living at 49, Glenforth Street, Greenwich. Further research shows that this was Joseph Todd Eltringham the youngest of Elizabeth’s siblings bn 1877. Joseph was married in 1929 to a widow, Ethel Robbins, who had eight children by her first husband. They had no further children and Joseph died in 1948 in Greenwich.

Joseph’s parents were John Cook Eltringham and his wife Jane. Could this be the same John who deputised for her father at Elizabeth’s wedding?

Sadly it seems that Elizabeth and James did not have any children.

The death of Elizabeth’s husband – and her admission to the Manor

On 9 March 1907 James died suddenly “at the works of the South Metropolitan Electric Light Company Ltd” and his probate shows that he left Elizabeth £333.12s which today would be equivalent to £51,252 which explains why when Elizabeth was admitted to The Manor Asylum on 21 Oct 1907 she was admitted as a private patient. Actually, now that we have access to the Manor Asylum Private Patients case book, we discover that Elizabeth had already spent 6 months in Peckham House Asylum before being transferred to the Manor.

The date of the original order was 16 April 1907, four months after her husband’s death. Later in the notes it is suggested that her fits were caused by “shock at seeing her husband blown up in an explosion.”

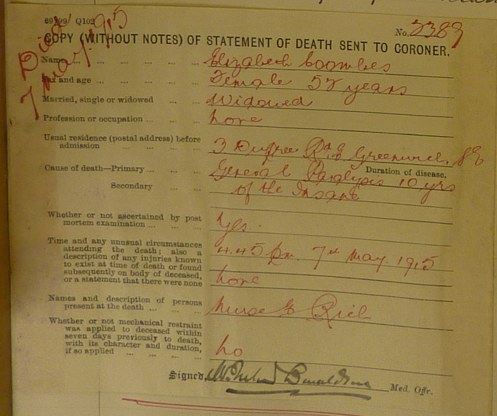

On her death certificate in 1915 it states that she had been ill for 10 years, 2 years prior to James’s death, so it is probable that with nobody to care for her it was felt necessary to place her in an asylum.

The Medical Certificate (Facts indicating insanity observed at the time of examination.)

Replies to questions with difficulty, short monosyllabic answers.

Cannot sustain a simple conversation.

However, Elizabeth states that her greatest trouble is money, “I haven’t had it yet and that worries me. She is obviously unaware that her finances are being dealt with by solicitors as you will see below.

Matron Rose Francis says, “She seems dazed and lost to her surroundings and was yesterday twice convulsed.

Elizabeth is said to have dark hair and brown eyes. To be “fairly nourished” Presents no other medical problems.

Mentally she is said to be simple minded, fatuous, rather forgetful and imagines she is in a story, she says she feels quite happy. Elizabeth has brought with her into the asylum, a collection of “rubbish, odds and ends and scraps of paper.”

It is noted that she says “she has lost the use of her legs for four years.” She suffers much in her head and has forgotten why she came here.

A note in October 1907 says that “she still claims to be very clever and is much pleased with her surroundings. On one occasion she took the ring from her finger and placed it on her toe” General health, moderate.

In November Elizabeth had a “slight convulsive seizure, she was dazed afterwards and was removed to ward E to sleep under constant observation.”

No further seizures are noted that year but her general health is now poor.

1908, January finds Elizabeth working on the ward, but by March her mental health is deteriorating. On the 26th she has a “slight convulsion.”

June 9th Simple minded, dull and confused. “Cries at times without ascertainable cause. Memory and intelligence becoming more affected. Articulation is very suggestive of G P I” (General Paralysis of the Insane.) “dementia, weakness, speech and hearing difficulty, and other symptoms associated with the late stages of syphilis.”) Another seizure on June 23rd.

Throughout the rest of the year there were no seizures or changes recorded.

In Jan 1909’s Special report and certificate. General Paralysis of the Insane.

“says she is very strong and clever and feels happy.” Grandiose delusions. She says she has got £300 here and has large estates. (We now know that she did indeed have a sum of about £300 but obviously she does not understand that the money has been paying for her to be cared for at Peckham House and The Manor.) Well marked physical signs of the disease. Poor health.

Elizabeth continues to deteriorate and the final note in the Manor’s record is for Nov 20th. “Whilst returning from the general bath room she fell in the corridor and sustained a simple fracture of the left tibia, just above the ankle and witnessed by Nurse F Langley.

Sadly this is where the records stop and we have over two blank years, although we do have her recorded on the 1911c as (E C) where it states that she became ill at the age of 44yrs which seems to agree with the notes.

We find Elizabeth (E C) on the 1911 Census for the Manor where it states that she became ill at the age of 44 years which seems to agree with the notes.

We must assume that by 1912 the money had run out and she was “transferred from private to pauper” which is where we can pick up her story.

The other people mentioned in the visitors’ book are Solicitor George Whale from the London and County Bank Chambers, Woolwich and Herbert London, High Leigh, Mycena Rd, Westcombe Park, E8 “Late Gaurantor.” (their spelling) Presumably these gentlemen took care of Elizabeth’s finances whilst she was a private patient although neither ever visited. The other family member to visit her was her sister Jane Steinson who lived at 7, Trinity Street, South Shields who, along with Joseph visited her several times during her stay.

Elizabeth’s health deteriorates

Following her transfer we first hear from the doctors on 12 June 1912 when we are told that she is “in the last stage of general paralysis, bedridden and very feeble.” In December of that year he says that she is “quite lost to her surroundings, in the last stages of her disease”.

Sadly there is no improvement and in March 1913 her report states “General paralysis of the insane, last stages. Bedridden, needs constant care.”

In December 1914 “she is still alive but much demented and oblivious of her surroundings.”

On 6 May 1915, “had a seizure last night; on 7 May “Much worse”; on 8 May “died yesterday afternoon 4.45pm.

Elizabeth was buried in Horton Estate Cemetery on the 13th of May 1915 in Grave 1779b.

Elizabeth’s siblings.

All of Elizabeth’s siblings except Joseph lived out their lives in the Gateshead area which makes her sister Jane’s visits very special considering the journey.

All married, several more than once, and all the men worked in the heavy industry of the area, in iron foundries, shipyards and mining.

Author’s note

Health checks in the Manor appear to have been carried out on a quarterly basis with no additional notes in between; sadly Elizabeth seems to have already been in a very poor state when she was transferred and deteriorated slowly over the next three years until her death. Once again we find the language used rather shocking to our modern sensibilities and I wonder if the doctors were aware that there was some truth to her “money worries and grandiose ideas.”