b.~1871 – d.1915

The story of Walter Beadon is among the saddest of the many troubled souls who ended their days at Long Grove Hospital and subsequently received a pauper’s burial and grave in Horton Cemetery, Epsom. Until now a forgotten man in a forgotten cemetery.

It is also a story that brings sharp focus to the grinding poverty and hardship of the Victorian London’s poor. Walter and his family could have stepped straight off the pages of a Charles Dickens novel. Walter and his ilk too often ended up broken by the miserable existence they endured, and it was for them, the socially submerged of London, to a great degree, the Epsom hospitals were created. The Cluster gathered these people up to treat their tortured minds and provide refuge from the wretchedness of their lives.

To understand better Walter and his environment we should first look at his forbears. His grandfather, William Robert Beaton, was born in 1810 in London just five years after the Battle of Trafalgar. He is recorded as a perfumer or performer. The former being the most likely. In 1840 William marries Jane Acton Dunston but sadly she dies just five years later

Soho life

Emma, Walter’s mother, is born between 1851-4 to a new wife or partner and she is given the second name Jane, presumably in memory of William’s lost wife. She is baptised in St. Anne’s Church in Soho. This is an area of central London that has gone in and out of fashion over the years. At the time of William, Emma and Walter, it was deeply out of fashion. The shocking memory of a cholera outbreak in the area lingered for decades. In 1854, when Emma was just three years old, 600 people in Soho alone perished from the disease in just one month. The area was poverty-stricken and known as a hub for prostitution, petty crime and packs of roaming street children. The reputation that Soho tried hard to shed a century later was formed in the period of Emma and William’s hard lives.

In the workhouse

On May 3 1869, Emma is still a teenager but fending for herself. She enters the Broad Street Workhouse in Holborn that night and promptly gives birth to a baby she names Henry. The workhouse record the child as “illegitimate”. Baby Henry only survives for 12 weeks and in the months that follow his death Emma is in and out of the Holborn workhouse. On one entry, at least, she has been admitted by a doctor. One can only imagine the mental anguish she is suffering on top of the daily battle to survive. Interestingly she is telling the workhouse she is four years older than she really is. Perhaps she is frightened of being committed to an institution of some kind.

Her next child, Walter, the main subject of this story, was born in 1871 into such poverty and chaos that his birth event has eluded officialdom completely.

In the 1871 census Emma and Walter are picked up at 22 Mercer Street, in Covent Garden. Emma lists her occupation as a servant. Walter’s birthplace is noted as St. James’, Westminster.

We have to wait six years for Walter next to surface on record. He is six years of age and is admitted to the Westminster Union Workhouse on Poland Street. He is with his mother who gives her name as Emma J and describes her occupation again as a servant. In 1877 on Monday, 14 May, Walter is back in the same shelter on his own. This begins a sad, relentless pattern of the family going in and out of the workhouse. It is their crutch and their last resort for food, warmth, and shelter.

Sometimes Walter is admitted by himself, still not much older than a toddler, and at other times with his baby sister Annie, who was born on May 8, 1877. As with Henry no father is listed. Emma ensures Annie is baptised and on that form she lists as a servant and provides an address as 3 Hornton Place, Kensington. Bearing in mind Kensington being a far more prosperous part of London and the Beadons use of workhouses at this time perhaps Hornton Place is the house where she worked? Workhouse admissions are often on Fridays suggesting Emma has ensured her children are fed and have a roof over their heads even if she does not. Perhaps she is working somewhere? This almost itinerant existence persists for some years.

Also, in 1877 the children are admitted to the St James’ School in Tooting. The school belongs to the Westminster Union Workhouse and takes the children of the homeless and destitute. It seems from the admissions and discharge pattern that the two children are taken there and removed from several times a month. It is unlikely that Emma had the funds to take a tram or a train and therefore the family could be regularly walking from Soho to Tooting and back two or three times a week. This sad routine continues for, at least, three years.

Suffer the children

Tragically Walter’s baby sister Annie dies in January 1880 in Wandsworth suggesting that whatever happened to her took place at the school. We can only guess at this stage what the circumstances of that death were. In the 1881 census Walter is still resident at the St James Road Industrial School. We can assume that during this period Walter is at least sheltered from the elements and being fed and educated.

On 3rd December 1880 Emma gives birth to a son and a brother for Walter. She names the baby James. Another sister, Eleanor, follows in 1884 and in both cases no father is indicated, and no adult male ever seems to enter the workhouse with the family. Eleanor’s birthplace is given as Kensington. In November of 1884 Emma is using the Britten Street, Chelsea workhouse with Eleanor and James. Walter is still living in the St James’ Road Industrial School. In April 1885 the family is broken up again in the most desperate of ways: Eleanor dies, and James is put into the Beechholme Children’s Home in Banstead, Surrey.

In the years between the 1881 and 1891 census we know little of Walter but can assume from what happened later that as a teenager he led a tough, poverty-stricken existence very likely fending for himself on the dangerous streets and dark alleys of Victorian London.

In 1880 there is a curious entry on The Old Bailey records. A Walter Beeden (sic) is listed in a group with four other males who were acquitted on charges of burglary and larceny. Could this be our Walter on trial at The Old Bailey at the age of nine? Children were still being tried and imprisoned as adults at the time although there was a gathering movement against it and the practice was dying out. Shockingly, only 50 years earlier a 12-year old boy was sentenced to death at the Old Bailey and hung. Was Walter running with a street and dwelling robbery gang? The sort of gang that inspired Charles Dickens to create Fagin and The Artful Dodger in Oliver Twist?

The Old Bailey

There is another Walter Beeden around at the time who was born four years before our Walter and has a similar workhouse admission and discharge pattern to his life but there are no further visible criminal records of him. The four other acquitted names listed alongside this Walter all have corresponding names born around the same time as Walter and have either criminal or London workhouse backgrounds.

Life of crime

Giving more credence to the theory is what Walter does next. When we pick him up in June 1890, as a 19-year-old youth, he is sentenced at The Old Bailey to 9 months in prison for burglary. This offence was unlikely to have been his first.

52. WALTER BEATON (21) Pleaded guilty to burglary in the dwelling-house of William Clark, and stealing a tureen and other articles.— Nine Months’ Hard Labour.

Proceedings of the Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey), 23 June 1890

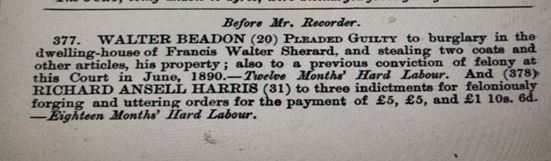

Walter would have barely walked out of the prison gates when he is back at the Bailey again in April 1891. This time he is sent down for a year’s hard labour for housebreaking. Only days before he was recorded on the census in Holloway Prison in London, where he was presumably on remand awaiting the Old Bailey case. He gives his trade as a labourer and his birthplace as Camberwell.

The below press cutting illustrates how Walter has entered the house of a jeweller in Trinity Road, an address very close to Wandsworth Prison and his old school.

Walter’s claim to only having wanted to eat is supported by the disturbed bread and butter meal he had made, although he has stashed two coats in an outside passage. The press report finds humour in the incident but had Walter not acted in the submissive way he did the story could have ended very differently – perhaps, with the loss of life.

Hard labour was not a throwaway remark. The prisoner would be required to walk a treadmill in his cell that had no end product for hours on end. Alternatively, he might be forced to turn a handle in their cell known as the “crank” for most of the daylight hours. This would be tightened up by the warders to increase the strength needed to turn the handle. It was from this pointless and cruel practice the nickname “Screw” evolved. These punishments were finally abolished in 1898.

Again, Walter had been released only weeks when he found himself back at the Old Bailey. On May 23 1892 the highest court in the land sentences him to 18 months imprisonment for burglary and felony. This time Walter has returned to somewhere he knows – the St James Industrial School in Wandsworth and breaks into the residential rooms of master George Harold Quaint. As Walter has only been left 4-5 years he may well have known the teacher and his room well.

583. WALTER BEADON , Burglariously entering the dwelling house of George Harold Quaint, and stealing twelve pieces of paper and thirty-six postage stamps his property.

Proceedings of the Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey), 23 May, 1892

Hard times and hard labour

Walter pleaded guilty to this and two other indictments. The speed of Walter’s re-offending and his return to the only home he had ever known suggests that he was deeply institutionalised. This is a posit supported by the fact that on January 9 1894 having been at liberty for about eight weeks he is in court again and receives his longest tariff of three years. His scheduled release date of 11 June 1896 means he will spend the best part of six years behind bars, walking treadmills and turning cranks.

As a regular now in at His Majesty’s pleasure the authorities take the opportunity of examining him physically and make the following almost anthropological observations about Walter:

Scar on right buttock; dark brown hair; blue eyes; 5ft 8 inches tall; scald on chest and left arm; tumour on centre of breast; lump on right cheek; fleshy mole on front of neck; small mole on right forearm; large indent on side of head.

Police would not have had much trouble identifying poor, battered Walter.

That final identifying feature gives cause for concern. What accident of birth or life could have caused such an affliction and did such a “large indent” head injury contribute to Walter’s later mental illness?

It is possible Walter kept out of court and prison afterwards but by no means certain. There are no further criminal cases identifiable online. In 1898 and 1899 he is picked up at 63 Tilson Road, Camberwell. One can only hope he did enjoy, at least, some years of a quieter more stable life.

Meanwhile in 1896 his brother James is discharged from the children’s home in Banstead straight into the 8th Hussars regiment of the army. He is only 15! However, the trajectory has kept him from following a similar life to that of his unfortunate brother. His subsequent army record reveals that “He was four feet eight inches tall and was of fair complexion with blue eyes and light brown hair. He had a large scar on the front of his neck.”

Sadly, in September 1906 Walter is admitted to an asylum in York. How Walter ends up in York is, for now, a mystery. He stays there until 1 October 1907 on which day he arrives in the bucolic Surrey countryside of Epsom at Long Grove Hospital. Hospital records suggest that Walter’s “infirmity” came on in 1896, presumably soon after his prison release. He lives at Long Grove until his death eight years later, aged just 45, in 1915.

Walter BEADON is buried on 12th July 1915 in a pauper’s grave (1803b) at Horton Cemetery, Epsom. Poor Walter never stood a chance in life.

Another tragic postscript is that Walter’s brother James died within a year of Walter in 1916. He fought in the Boer War and survived but decided to stay in South Africa following the conflict’s cessation. In WW1 he signed up to the South African Army and died in battle in German East Africa, now Tanzania.

The Commonwealth War Graves web site states that James Beadon’s body was buried by the Lumi river on the 8th of March but was later exhumed and buried in Taveta Military cemetery in Kenya. He was short of stature, but not short of courage.

AUTHOR COMMENT:

The attached press cutting from 1892 shows that Walter’s mother Emma was no stranger to the police, the courts and prison. Here she is smashing a pub window in the early hours of the morning and receiving two months hard labour, after just being released from two months hard labour! This sad pattern of repeat offending was being passed down the generations. Remarkably, Emma lived on to 1927 when she died in Kensington, aged, at 85 years old, at least, in a workhouse hospital.

I believe it is possible that Emma Beadon was a prostitute. The location, the lack of a male father or partner figure throughout the story and the five, at least, pregnancies suggests this to me.