b.1842 – d.1908

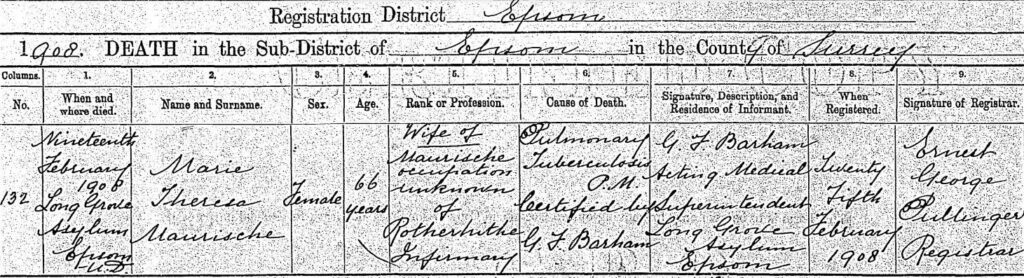

Marie Theresa Maurische died on the 19th February 1908 in Long Grove Asylum and was buried in Horton Cemetery on the 25th February. Her death certificate records that she was the wife of Maurische ‘occupation unknown’ and that she was ‘of Rotherhithe Infirmary’. The cause of her death, confirmed by post mortem, was ‘Pulmonary Tuberculosis’. Her age was given as 66 making her estimated birth year 1842.

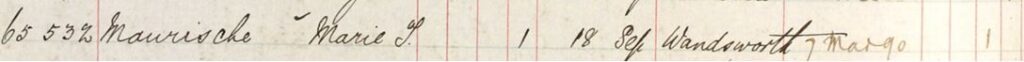

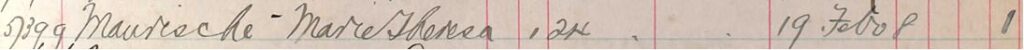

The Lunacy Patients Register records her admission to Wandsworth Asylum, or more formally Surrey County Lunatic Asylum, in September 1880 when she would have been 38.

There is a possible entry for Marie in the 1881 census for the Surrey County Lunatic Asylum of a female patient with the initials MTM, married, age 39. No birthplace is given.

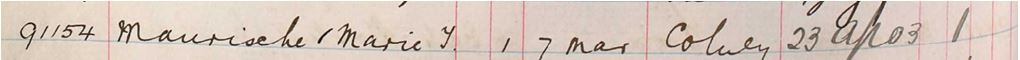

Marie was discharged from Wandsworth Asylum on 7th March 1890 and the Register shows that she was admitted to Colney Hatch Asylum at Friern Barnet on the same date.

No entry has been found in the 1891 census for Colney Hatch Asylum that could be Marie. There is however a possible entry for her in the 1901 Census of a female patient with the initials MM, single, age 59, birthplace London.

The Register shows that Marie was discharged from Colney Hatch on the 23rd April 1903 with the reason given as ‘Reld’ [Relieved]. After 23 years of incarceration, she must have been transferred to another asylum but as the Register for 1903 is missing we don’t know where.

The next time that she appears in the Register is when she was admitted to Long Grove Asylum on the 24th September 1907. This would have been shortly after the asylum opened.

The Register records her death at Long Grove on the 19th February 1908 which is confirmed by her death certificate

Initially, these were the only records of Marie’s life that could be discovered. Despite having a distinctive surname – Maurische, which in German means Moorish, as in the North African influence found in southern Spain – no marriage or birth certificate is to be found nor any record of an admission to the Rotherhithe Infirmary. Only one other person has been found with the same surname: a John Maurische who was charged with pig stealing in New South Wales in 1880.

Having exhausted what could be found from Marie’s death certificate and the scant information available online our attention switched to what might be available in the archives.

Surrey History Centre does hold a few case books for the Surrey County Lunatic Asylum but unfortunately the one that would have covered Marie’s admission in 1880 is missing.

However, the case files for patients at Colney Hatch Asylum do still exist and are held at the London Metropolitan Archives. A visit to look at those for patients admitted in March 1890 found the notes for Marie.

Marie’s Case Notes

The first section of the case notes is a copy of the statement made by R. J. Shepherd MRC, Medical Officer of the St Olave’s Union Infirmary, Rotherhithe to explain why Marie was considered insane. The main reasons seem to be that she ‘maintains an attitude of listless apathy’ and is ‘sunk in her own gloomy reflection’.

He says that when her attention is demanded she is ‘peevish & irritable’. It appears she had been refusing to eat and there is a suggestion that she may have been force fed. Dr. Shepherd’s remarks are supported by comments from a Nurse Bellamy who was in charge of the ward at the infirmary where Marie was a patient.

Dr Shepherd ends his comments by saying, ‘I do not know Italian & have been unable to get at the state of her mind.’ It will become apparent that Marie may not be able to understand English and that those treating her do not know what language she speaks.

The next section of the notes was completed by an unidentified asylum doctor on 7th March 1890. Her form of disorder is recorded as ‘Mania’. [Mania was one of the three main diagnoses applied to mentally ill patients in the 19th century, the others being Melancholia and Dementia.]

She is described as being free from injuries and thin but in a good state of health. ‘She sits in the same place all day except when roused and apparently takes no interest in any of her surroundings.’ The doctor says that ‘she is probably Jewish (German) and it is very difficult to make her understand or to understand what she says.’ [Marie Theresa are not names that would indicate a Jewish origin; they suggest that it is more likely that she was Catholic.]

Three days later, on 10th March, it is recorded that she is ‘clean, quiet, and orderly but obstinate at times, is listless and unemployed, chatters and laughs a little to herself, but is generally vacant and apathetic.’

In May, it is recorded that ‘she sits all day upon the settee doing nothing, seldom speaks unless roused up, when she is apt to [be] spiteful & disagreeable, as [sic] times chatters volubly in some unknown tongue, probably a German patois.’

A note in September in the hand of a new doctor records that ‘she does not appear to understand a word of English. Is still dull and depressed. Health fair.’

Notes continue every few months, nearly all repeating the same comments. Her health is fair but her mental condition is unchanged.

In January 1900, nearly 10 years after Marie’s admission to Colney Hatch, her notes are continued in a new casebook, the space in the original one having been filled up. The first note in the new book is typical of those that follow: ‘Silly and incoherent. Noisy at times. Hears voices. Clean in habits. Unemployed. In fair health.’

Similar notes follow until 23rd April 1903 when it is recorded that she has been transferred to Birmingham City Asylum, Winson Green. This answers the question posed by the missing Lunacy Patients’ Register for 1903. [See the note below about the possible reason for this transfer.]

Finding a Photograph of Marie

However, having built up a mental image of Marie from the notes written by the asylum doctors we now have to reconcile that with an actual image of her. On the page facing the notes, hidden behind a form referring to another patient, there is a photograph of Marie. We can be sure this is her because the number on the photograph ending 0623 matches Marie’s number in the casebook, 10623.

Marie appears to be neatly dressed. Her shawl is held together with an elaborate clasp, and she is wearing a delicate coral necklace. Her hair is pulled up in a neat bun. Her expression is hard to decipher. She looks directly at the camera, or the person behind the camera. Possibly there is a hint of smile. Perhaps there is also a wariness.

The case notes for Birmingham City Asylum which would record Marie’s time there do exist at the Birmingham Archives and Heritage Service but are affected by mould and not accessible.

The case notes for Long Grove Asylum, her final place of incarceration, have been lost apart from a very few.

Although the Colney Hatch case notes tell us something about Marie we are still left with questions. Where did she come from originally? Did anyone ever discover what language she spoke? Did she ever understand why she was confined in the asylum? Can we be certain that any of the little factual information that was provided by the Rotherhithe Infirmary and then followed her through the asylum system is reliable – her name, her age and marital status? Alas, this is all likely to remain a mystery.

Additional notes:

Colney Hatch Asylum had been opened in 1851 as the second pauper asylum for the old county of Middlesex. By 1890, when Marie moved there, it was seriously overcrowded and conditions were considered to be very poor. In 1896, the total number of inmates was 2,584 and a temporary building made of wood and iron was constructed to house 320 chronic and infirm female patients.

Responsibility for the asylum passed to the London County Council in 1899. In January 1903 the temporary building caught fire and 51 women inmates died in what was called the worst disaster in English Asylum history.

It is possible that Marie’s transfer from Colney Hatch in April 1903 to Birmingham was a consequence of the fire and the need to reduce overcrowding.

Tuberculosis, the recorded cause of Marie’s death, was endemic in pauper asylums in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

A report in the British Medical journal in 1902 on a committee set up to consider the issue of tuberculosis in asylums points out that while it was well-known that tuberculosis, and particularly pulmonary tuberculosis, known at the time as phthisis, was common the extent of its prevalence was not sufficiently realised by the local authorities responsible for the asylums.

The committee report made the case for a systematic approach to the identification of patients who were infected on admission or who became infected while in the asylum, and their isolation. Emphasis was given to avoiding over-crowding and improving ventilation.

There was particular concern about the spread of the disease by spitting. It was not until the 1950s with the advent of antibiotics that a cure for tuberculosis become possible. Prior to that the main treatment that was offered was exposure to the open air. A vaccine against tuberculosis had been developed in France as early as 1921 but was not taken up widely elsewhere until after the Second World War.