b.1850 – d.1908 The Worst and Wickedest Woman in London

Introduction

The life of Tottie Fay has been pieced together from numerous sources – initially through newspaper articles from the reporters whose jobs were to attend the many magistrates’ courts in London. Unfortunately, these court proceedings have not been digitised and we have relied on the first-hand accounts of the reporters themselves, albeit somewhat embellished I would imagine.

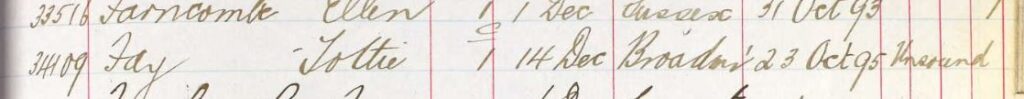

As Tottie’s misdemeanours became more serious, she was often committed for trial at the London Sessions in Clerkenwell, where records have been digitised to some degree. Once Tottie had entered the judicial procedure of imprisonment, official documentation is available. When Tottie was declared insane and committed to incarceration in mental asylums, several records give us a picture of her journey towards her eventual demise. Tottie assumed many, many different names. Thus, we have as yet been unable to find a birth registration, nor any record of Tottie Fay on any census return.

I challenge you, upon reading her story, not to feel admiration for her courage, in the overwhelming face of adversity, and to feel compassion in droves for her life-story and eventual fate. To be incarcerated in the dreadful Millbank Prison, then Wormwood Scrubs, followed by Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, Colney Hatch Asylum, Fisherton Asylum, Colney Hatch Asylum (a second time), then finally Horton Asylum. Tottie you were a survivor.

From the Register for Habitual Criminals, 1892 we can build a picture of Tottie Fay. Her complexion was Rosy, her hair Dark Brown, her eyes Grey, height 4’11”, shape of face Oval, and her birthplace London.

A colourful life

Tottie Fay was born in London about 1850 under a name we may never know.

The first time we hear of Tottie’s fall from grace was in August 1879 when she would have been about twenty-nine. She was convicted at Clerkenwell Court and sentenced to four months imprisonment at Millbank, on the charge of Larceny and Receiving stolen sheets under the name of Lillian Cohen.

In March 1886, using the alias of Amy Anderson, Tottie is convicted at the Middlesex Sessions, held at Clerkenwell Court, of stealing surgical instruments and sentenced to three months imprisonment.

One year later, from a report in the Pall Mall Gazette dated 7 March 1887, Tottie appears before Mr. Mansfield at Marlborough Street Magistrate’s Court. The paragraph does not state the charge, but the magistrate refers to her as the London “Rosière of Vice”, (rosière {f} young girl recognized for her virtue; vice {noun} immoral or wicked behaviour often involving prostitution, pornography, or drugs), declaring her to be the worst and wickedest woman in London and sent her to prison for one month. Her age is given at thirty which would give her date of birth as 1857. Her aliases were stated as Lily Cohen, Tottie Fay, Lilian Rothschild, Violet St. John, Mabel Gray, Maud Legrand and Lily Levant. Quite a list! It is hard to comprehend just what Tottie had been up to as the reporter states “It would be interesting to have an accurate biographical and scientific diagnosis of this superlative specimen of human depravity”. Harsh words indeed.

(c) British Library Board

A report in Reynolds’s Newspaper dated 14 April 1889, details Violet St. John, better known as Maud Rothschild or Tottie Fay, appearing before Mr. Hannay at Marlborough Street Magistrate’s Court on a charge of drunk and disorderly in St. James’ Square. Her appearances at this court are so numerous that a special book is kept for them. She was given the choice of paying a fine of 40/- or of one month in prison.

Two months’ later a report in the Illustrated Police News dated 22 June 1889, Lily de Terry, (Lilian Rothschild, Tottie Fay, Maud Grey, plus other aliases), aged twenty-two of Gilbert St, Grosvenor Square, was charged at Marylebone Police Court with being drunk and disorderly at Porchester Road, Paddington on 8 June. According to the gaoler her last appearance at Marylebone was in 1886. Tottie became hysterical during questioning and said she had had her purse stolen but then retracted this. She said that she was a lady by birth and, whether in drink or not, could positively not use bad language. She had become low-spirited after the death of a sister and had had a little drink, a story of being bereaved that she would use again! The magistrate Mr. De Rutzen took pity on her since she had been in custody for some days between being arrested and the court appearance. He gave her the choice of a fine or one day’s imprisonment. She replied, “Heaven bless you”.

According to Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, dated 25 August 1889, and the Illustrated Police News, dated 31 August 1889, Tottie’s next court appearance was in Westminster under the name of Mabel Granville, (Tottie Fay, Lillie le Grand, Lily Lorraine, Grace Cohen, &c.) aged twenty-two, actress, of Elaine Grove, Haverstock Hill was charged with being drunk and disorderly and using obscene language at Belgrave Street. After consuming eggs, bread and butter and pots of tea at a pastry cook’s shop opposite the Grosvenor Hotel, Belgrave St, when asked to pay she had become abusive, and the police had been called. Tottie denied the charges using the same sob-story of bereavement. When questioned by Mr. D’Eyncourt she confirmed that she was not an actress. The assistant gaoler said that Tottie had been repeatedly charged at this same court under assumed names for being drunk and disorderly. She said, “Please listen to me gentlemen, I have been trying to keep out of trouble”. She was fined 14/- or fourteen days imprisonment.

Regrettably within days of the previous court hearing, Tottie’s next breach of the peace landed her in a lot more trouble. Her court appearance at Bow Street Police Court was reported in no less than five newspapers – The Morning Post, dated 3 Sep 1889, the North-Eastern Daily Gazette, dated 4 Sep 1889, the Graphic: An Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, dated 7 Sep 1889, the Illustrated Police News, dated 7 Sep 1889, and Reynolds’s Newspaper, dated 8 Sep 1889. The charge was for being drunk and disorderly. Tottie, (alias Mabel Gray, La Petite Grace, Violet St. John, Maude de Rothschild, Mabel de Granville, &c), had tried to force her way into the lodgings of Mr. Armstrong in Southampton Row where he had just entered using his key. The Bow Street court gaoler told the court all about her latest ruse of arriving at an hotel with an almost empty box, supposedly representing luggage, securing a latchkey, proceeding to a London theatre in full evening dress and putting on a show of great excitement, lamenting the absence of her carriage and footman, and that she cannot get home as she has no money, thus eliciting sympathy from some members of the public. When not drunk she plays her part so well that there is always some simple-minded gentleman to pay her cab fare back to her hotel.

In this case she was drunk, trying to force herself on Mr. Armstrong, telling him that she was a stranger in this part of London, and could he tell her where she could find a respectable hotel. He told her he did not know the neighbourhood. Tottie tried to force her way past him into his lodgings. He managed to push her away and closed the door. Tottie commenced to hammer on the door using the knocker creating a great disturbance. He opened the door and waited outside for the police to arrive. She tried to get him to part with some money for a ‘cab fare’ which he refused. Once the police arrived her whole demeanour changed proceeding to use indecent and disgusting language. At the hearing Tottie entered the dock in her usual simpering semi-hysterical manner, dressed in a dirty, gaudy old ball dress with a low white bodice, the court gaoler saying that such a costume was part of her stock-in-trade. She also wore a profusion of rings. The court gaoler also said that Tottie had been charged at every court in London. Mr. Bridge, the magistrate, asked him whether anything had been done to rescue her? In reply he said, “A Jewish lady from Kensington took a great interest in her and took her to a home. She stayed about a fortnight, and during that time her behaviour was very bad”. To Tottie the magistrate said, “My experience of you is that I cannot believe a word you say. I believe your story to be as wicked and evil a lie as was ever told in this world”. He was safeguarding the public interests when he ordered “La Petite Grace” to find two sureties of £20 and be of good behaviour for six months. One reporter concluded, “It is to be hoped that we shall not hear any more of Tottie until the beginning of next March (1890) – and not even then”. Tottie reluctantly had to accept imprisonment being unable to find the sureties. She spent the next six months in Millbank Prison from September 1889 to March 1890.

Sadly, upon her release from Millbank Prison, Tot Fay, alias Amy Anderson, Maude Rothschild, Mabel Gray, &c., was soon back in the dock at Marlborough Street Police Court on a charge of fraud and felony. She had earlier been remanded to await the attendance of the Bow Street Court gaoler, and the Matron at Millbank Prison to provide more information. Reynolds’s Newspaper, dated 18 May 1890, reports that Tottie entered the dock carrying a bunch of artificial flowers, beneath which she had stealthily concealed a little brown loaf and some cheeses, her luncheon, brought from the prison. The gaolers took these items from her. The reporter states, “Her eyeglasses, instead of being perched on her greasy nose, were now suspended by a gilt chain at her side, and over a black glove on her right hand she wore a large paste diamond ring. She wore a tawdry light blue ball dress, a purple-brown silk costume and a jaunty cricket cap with a bunch of lace on the top of it.

The assistant gaoler at Bow Street Police Court said that Tottie had been charged there at least twenty times, always in different names. Ever the joker, Tottie piped up that she did not think it was exactly twenty times – “perhaps it is only nineteen”. The gaoler also recounted how in November 1888, after having been remanded from week to week, a lady interested herself in her welfare, and she was sent to a home at Kensington. After remaining there until 4 December, the lady came back to the court and asked that Tottie might be put under the charge of the police again, as she was dirty in her habits, pugilistically inclined, and entirely unmanageable. In fact, the other people in the home could not do anything with her. Again, she was placed in the dock, and the magistrate Mr. Bridge, in his leniency, ordered her to enter into her own recognisance of £10, and so Tottie regained her liberty.

The prison wardress from Millbank said that she had known the prisoner since 1879 and gave details of three earlier stretches at the prison.

In summing up, the Marlborough Street magistrate, Mr. Newton said, “Twenty times at Bow Street, thirty-one times here, and on many other occasions at Westminster, Marylebone, and elsewhere. Your career must be stopped. You stand charged with obtaining food by fraud and robbing Mrs. Green of clothing valued at £2. What have you to say?” Tottie replied, “Here are two letters – one from a gentleman who has my luggage, and the other is from myself. I am innocent of this charge. Oh dear, oh dear! I was going to ask you, sir, not to commit me for trial. Don’t do that, good, dear man, as a long imprisonment and unladylike society, you know, might injure my health”. This plea fell on deaf ears and she was committed for trial.

From the Clerkenwell Court records – on 19 May 1890 Tottie Fay, using the alias of Dolly Le Blanc, was convicted of Fraud at North London Sessions and sentenced to six months imprisonment. She obtained goods by means of false pretences.

The Morning Post, dated 28 May 1890, provides a little more detail. Dolly Le Blanc obtained food to the value of 3/-, and a bonnet and other articles valued at £2, with intent to cheat and defraud. Mr. Browning, from the Alhambra Theatre, where the accused had been a frequent visitor, gave evidence contradicting her statement that she was engaged there as an actress. Further evidence showed that on the morning of the 2 March Tottie appeared at the house of Mrs. Green in Hinton Street, and stated that she had an engagement at the Alhambra, that she had only just arrived by the night express from Paris, (disproved by another witness), and had not had time to change her dress, but her boxes were at Victoria Station. She was given some breakfast, and was also provided with boots and other articles by Mrs. Green. She had breakfast the following morning, then went to Victoria Station with Mrs. Green’s son. Instead of collecting her luggage she wrote a note to Mrs. Green to the effect that she would call and see her. A disappearing act! The jury found her guilty. Detective Gregory stated that he had known her as a disorderly character for eighteen years, and Inspector Anderson proved two former convictions for felony. Tottie was sentenced to six months imprisonment with hard labour.

Within months of her release from Millbank Gaol Tottie was back in the dock at Bow Street Police Court. The Daily News, dated 7 January 1891, reports that Violet Le Bell, otherwise Le Grand, better known as Tottie Fay, was charged with disorderly conduct and using obscene language in Montague Place, Russell Square. Tottie used the same tactics she had tried eighteen months previously which had landed her in the same court and a six months’ gaol sentence. She tried to enter a gentleman’s house on the pretext of losing her latch-key and missing the last bus home to Bayswater and not wanted to disturb her poor ma. When she was refused entry she commenced to abuse him in a manner that was described as being of the most filthy and disgusting nature. After being arrested and on the way to the police station she threw herself to the ground and became so violent that assistance had to be obtained to secure her. The gaoler told the magistrate that she was continually being charged with annoying gentlemen and had been placed under heavy bail for long periods. Every effort had been made on her behalf by charitable ladies. Tottie pleaded with Mr. Vaughan, “Oh, kind sir, give a most unfortunate young lady a chance of redeeming her life”, to which the magistrate replied, “You are, indeed, unfortunate. You have only just come out of prison, and everything has been done to redeem you”. He ordered Tottie to find one surety in 10/- to be of good behaviour for three months.

Tottie’s next reported escapade occurs just three months later and leads to a long prison sentence. This report from the Standard, dated 11 April 1891, relates to an appearance at Marlborough Street where Tottie is charged with fraud. At two o’clock in the morning Tottie blags her way into Fisher’s Hotel in Clifford Street, St. James, and tells the porter that she is staying in Room 5. (Luckily for her it was unoccupied at the time)! Tottie ordered and was served breakfast. By 8pm she had been rumbled and the proprietor asked her to leave and upon her refusal he called the police. Mr. Newton, the magistrate, remanded her for one week so that the servants from the hotel might be called.

A week later the Standard, dated 18 April 1891, continues the story. Tottie has given her name as Lily St. John, aged 25, an actress. She appears in the dock wearing a black dress and a red silk dolman, and around her neck was a large white worsted muffler, fastened with a brass brooch, and on the finger of one of her black gloves was an imitation diamond ring. She was bonnetless, and on her black locks were four large imitation pearls. The reporter seems to know more about Tottie’s background, writing that her right name was Amy Anderson, and her youthful habitat was the Seven Dials. The first alias under which she appeared at Marlborough Street court in 1883 was Maude Rothschild, then Lily Sinclair, Lily Levant, Maude Le Grande, Tot Fay, Dolly Leblanc, Maud Sinclair, and numerous others. Resuming the hearing and calling witnesses it transpires that during the afternoon Tottie ordered a chop, with tea and bread and butter, washed down with three bottles of ale. Tottie says, “and all this fuss over a paltry chop. If I had known it I would have gone in for a chicken and champagne”. She asks the hotel proprietor, “Don’t do anything rash”. Things don’t look promising when a female warder proved a previous conviction for fraud, then the court gaoler said that during the time that he had known her she had given seventeen different names. To make matters worse the proprietor of the Cavendish Hotel in Jermyn Street preferred a similar charge against Tottie for having obtained a bed and breakfast of ham and eggs. This time she rang the bell at 4:30 in the morning telling the porter that she had walked from St. James’ ball as her coachman had not come to fetch her. After hearing the evidence Tottie was again remanded for one week.

The Daily News, dated 7 May 1891, details when the case came to trial at Clerkenwell. A long list of previous convictions was proved against her, among them being one at these sessions last year for six months, when she gave the name of Dorothy Le Blanc. This time she was sentenced to twelve months imprisonment with hard labour at Wormwood Scrubs, (Millbank having been closed the previous year).

4 May 1891 to 3 May 1892 HMP Wormwood Scrubs, Du Cane Road, Hammersmith.

Sadly, 1892 marks the beginning of the end for Tottie, as within two weeks of being released from gaol Tottie is back in Marlborough Street Police Court. A report in Reynolds’s Newspaper, dated 15 May 1892, gives us the story. Tottie is charged with being disorderly and using obscene language in Portland Place at an early hour. Her appearance is described as – over an old dress she wore what was evidently a second-hand light silk dust cloak, trimmed with dirty white lace. On her breast were four large, silver-plated balls, said to be “badges of honour,” about the size of small oranges, and on her head was a grey fashionable hat, shaped like a bent tea-tray, and having on the left side of it, beside a mass of French, grey-coloured ribbons, a bunch of Marguerite daisies. Her jewellery consisted of some sham diamond rings of the best Brummagem make, and it could be seen that the oxide of the metal had stained the fingers on which they were worn. Her brooch and earrings were en suite, and altogether she presented a more respectable appearance than she had done on some previous occasions when charged. As she stood in the dock her huge dress-expander displayed to advantage, and she posed herself and, with eyes downcast and hands folded, she listened to the evidence as it was given against her. The reporter informs the reader that on each occasion of her having been charged, numbering more than thirty at this court alone, she has given different Christian and surnames, and her age has veered from eighteen to forty, then back to twenty-eight, then again to eighteen. From three different newspaper articles it is difficult to determine just what Tottie had been up to when she was arrested. Mr. Newton, the magistrate, said to her, “Now listen to me. If ever you misconduct yourself again I shall undoubtably send you to hard labour. You have been for years past and are a dangerous and mischievous woman. Now, take care what you do”. She was let off with a caution.

The caution fell on deaf ears since Tottie was back at Marlborough Street only two days later. Within hours of being cautioned on Saturday, she was charged for being drunk and disorderly in the early hours of Sunday morning in Albemarle Street. She had been annoying gentlemen, having been turned out of a private hotel. The magistrate, Mr. Hannay, sentenced her to 14 days imprisonment with hard labour. As reported in three newspapers – The Standard, dated 17 May 1892, the Birmingham Daily Post, dated 18 May 1892, and the Illustrated Police News, dated 21 May 1892.

(c) British Library Board

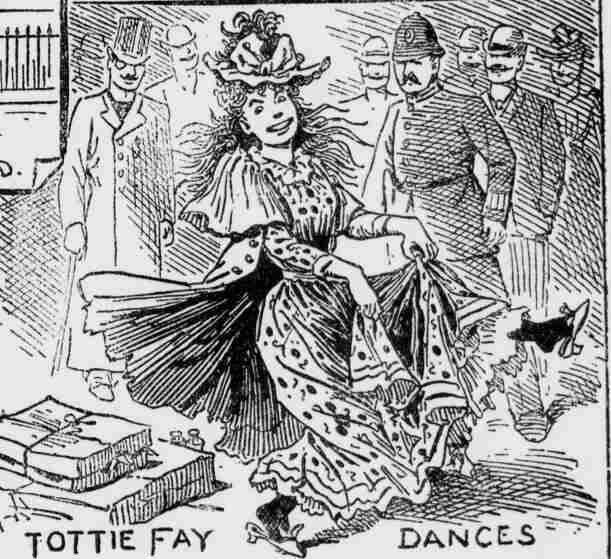

Tottie just cannot help herself, the downward spiral is slowly swallowing her, since she is back, as Lily Carlton, aged 26, an actress, of Camden Road, Camden Town, (Tottie is now over forty), at Marlborough Street, for the 39th time, charged with disorderly conduct in Oxford Street. Two similar reports in Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, dated 5 June 1892, and the Illustrated Police News, dated 11 June 1892, describe her appearance in great detail. She was wearing an exceptionally large light straw hat suggestive of the “Dolly Varden,” and decorated with a large bunch of imitation marguerites, on her feet a pair of white satin dancing shoes, which she took great care should not escape attention. A light-coloured waterproof concealed her dress, but its neck was open sufficiently to display a dirty and crumpled “dicky” adorned with a couple of cheap studs. As she stepped into the dock she handed to the gaoler, with a graceful sweep of the arm, a pair of opera-glasses and the familiar metallic tiara. During the hearing of the evidence Tottie shed tears profusely and maintained her customary attitude of supplication and injured innocence. The policeman said that she was dancing on the pavement in Oxford Street at twenty minutes to one in the morning and that a large crowd had gathered around her. Tottie was clearly drunk at the time. In the dock, theatrically wringing her hands, she said, “I have not a friend in the world, It’s cruel, it is. It’s cruel.” The magistrate, Mr. Hannay, learned that she had recently come out of prison after a 14-day sentence. He remanded her for one week.

A report in the Standard, dated 8 June 1892, and also in Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, dated 12 June 1892, shows that people do care about Tottie. At the court appearance, following her remand, Tottie was defended by Mr. Arthur Newton who had been instructed by a gentleman who had read and been touched by Tottie’s previous appeal of “I have not a friend in the world.” Mr. Newton pleaded on her behalf saying that yes, she had committed an offence, but considering her sad life, seven days in gaol whilst on remand would be sufficient punishment. The magistrate, Mr. Hannay, was unmoved saying, “It is one of these cases which are the despair of Magistrates. We have no power to retrain her from the impulses to which she is subject. When she is not sent to prison, she comes back immediately. I have known this woman for not more than two years, but I can see she is killing herself. She is prematurely aged already. In mercy to her, I must send her for one month.” The Weekly Standard and Express, dated 11 June 1892, adds that Tottie had sobbed during Mr. Newton’s address to the magistrate, and as she stepped out of the dock exclaimed to him, “Bless you”.

(c) British Library Board

Tottie’s next court appearance was the following month, one week after being released from one month in Wormwood Scrubs, again at Marylebone Police Court, and widely reported in three newspapers, Reynolds’s Newspaper, dated 18 Sep 1892, the Illustrated Police News, dated 24 Sep 1892, and the Newcastle Weekly Courant, dated 24 Sep 1892. The charge was of attempting to commit suicide in the Regent’s Canal. She gave her name as Lilian Vivian, aged thirty-seven, a governess of Kentish Town Road. Tottie was dressed in the same clothes as her last appearance in the same court five weeks previously. The arresting police constable was on duty at Gloucester Gate Bridge, Camden Town, and saw Tottie at two o’clock in the morning looking into the water. She then climbed on to the parapet of the bridge, but the constable caught hold of her. Tottie said, “Oh, do let me alone, I’m in low spirits.” He took her into custody and during the journey she expressed regret that she had not been quicker in her movements and would have been in the water before he arrived. In reply to the charge at the station Tottie said that she had only stopped to fasten her bootlace. She was drunk which she refuted by admitting to only having had two glasses of ale. The magistrate, Mr. Hopkins discharged her. Tottie replied, “Oh, thank you sir. God bless you. You’re a gentleman.”

Tottie’s notoriety is picked up by an ever-expanding array of newspapers and the next court appearance at Marylebone Police Court for being drunk and disorderly in the Great Western Road, Paddington, is reported in Reynolds’s Newspaper, dated 14 Aug 1892, the Northern Echo, dated 16 Aug 1892, The Hampshire Advertiser, dated 17 Aug 1892, and the Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle, dated 20 Aug 1892. Tottie’s appearance is described as wearing a very big-brimmed straw hat, looped up behind and on both sides, and an apparently new large plaid waterproof. On her wrists were flash, gaudy bracelets, of the commonest type. On entering the dock she bowed gracefully to the Magistrate, and then, craning her neck, stood erect, and looked disdainfully at the Police Constable who had arrested her, (difficult when you are only 4’11”)! He said that her found her in the Great Western Road drunk and using abominable language. Tottie pleaded with the magistrate, Mr. Hopkins, saying “But it’s quite a long time since I was at this court. Do sir, I mean your Worship, let me go this time.” His response, “You have had many chances, but you are absolutely and hopelessly incorrigible, and I sentence you to one month’s imprisonment.” The Northern Echo reporter amusingly said that Tottie Fay had again shed the light of her beaming countenance upon the otherwise sombre Marylebone Police Court, and previous to her retirement from public life for a month, had once more enlivened the dull routine of magisterial duty with a dramatic recital of her woes.

Tottie’s penultimate misdemeanour, just five days later, was reported by Reynolds’s Newspaper, dated 25 September 1892, charged at Marylebone Police Court with disorderly conduct and causing a crowd to assemble. She gave her name as Mabel Lorraine, a teacher. The arresting police constable found her in Bishop’s Road, Paddington at half-past twelve having an altercation with a cabman. He tried to get her to move on, she went a short distance but then turned and abused him, accusing him of stealing a ring off her finger. The magistrate, Mr. Cooke warned her that she would get into serious trouble if she did not stop behaving as she had done for some time past. He fined her 5/- or three days’ imprisonment.

A reporter paid this fine of 5/- in order to obtain an interview with Tottie, as reported in an article detailed below**

Within days Tottie had committed her last offence, stealing three pounds and ten shillings in gold, which resulted in a trial leading to a three-year prison sentence.

The Standard, dated 7 October 1892, gives us the story. John Hetherington, a traveller, was staying at the Temperance Hotel in Queen Square, Bloomsbury. He had an upper room in the hotel and was awoken at three o’clock in the morning to a loud knocking on the door. He opened the door to find Tottie standing dressed and with a shawl over her head holding a lighted candle. Tottie said, “I beg your pardon, I thought this was the waitress’s room. I feel so ill and want a drop of brandy. I have a room on the drawing-room floor and would be glad if you could get me a little stimulant. Say it is for yourself, as I should not like them to think that I wanted it.” Mr. Hetherington went down and asked for the brandy, and upon his return found that Tottie had disappeared, and that his waistcoat was missing from a chair. He found it under the bed with his empty purse from which was missing three pounds and ten shillings in gold. He gave the alarm but Tottie had left the building. Information was given to the police, and at nine o’clock that morning Mr. Hetherington saw Tottie at Hunter Street police station and charged her with the offence. Tottie asked him to withdraw the charge and she would return his money. She was found to have over two pounds upon her when arrested. Tottie’s story was that he had invited her to his room where they had smoked cigarettes and drank brandy together.

Tottie had been up to her old tricks again of duping her way into a hotel and securing a bed for the night. She had rung the night bell at two-thirty that morning, waking the night porter. When he reached the hall, he found that the cook had also been woken and had let Tottie in. She was in evening dress and was complaining of the cold. The night porter gave her a room on the first floor. He was woken again after about half an hour when Mr. Hetherington raised the alarm after the robbery. A police constable arrested Tottie at six-forty five that morning in Euston Road. Surprisingly Tottie said nothing when charged, but at the station said, “I would not be so mean as to do a thing like that. If I wanted to thieve, I should steal diamonds.” The Aberdeen Journal, and General Advertiser for the North of Scotland, dated 8 October 1892, carried the same story.

Tottie appeared at Clerkenwell Police Court where, after hearing that she had been charged and convicted of larceny on a previous hearing at the sessions, Mr. Horace Smith committed her for trial.

The Standard, dated 27 October 1892, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, dated 30 October 1892, and the Royal Cornwall Gazette, and Falmouth Packet, dated 3 November 1892, the Derby Mercury, dated 2 November 1892, and the Illustrated Police News, dated 5 November 1892, all print the story. Tottie was tried at Clerkenwell County Sessions by Sir Peter Edlin, Q.C., who was told about several previous convictions, and that there were innumerable others for drunkenness and disorderly conduct. In Tottie’s defence, Mr. Slade-Butler said there were certain charitable persons who were willing to put her into a home for inebriates, and asked for a postponement of sentence. Sir Edlin said, “With regard to that matter, it must be laid before the Secretary of State.” Tottie made a rambling statement, to the effect that all her misfortunes had arisen from drink. She was an “orphan young lady”, and could not endure solitude or eat prison food, and that she would lose her reason if placed in solitude. Sir Edlin said that it was useless to pursue that line of argument, and that the offence had been clearly proved, and was much aggravated by unfounded charges made against Mr. Hetherington. He sentenced her to three years’ penal servitude.

A column in the Northern Echo, dated 27 October 1892, whilst briefly reporting Tottie’s final conviction for larceny, also included some very interesting facts detailed below.

**the reporter who paid Tottie’s fine of 5/- interviewed her and the following was published in the Gospel Temperance Bells, a Newport teetotal organ, edited by Mr. R. Mildren.

“My real name is Lillie Carver and I am a Jewess. My mother lived at 22 Russell Square, and afterwards at 38 Great Coram Street. My sister Violet and I used to go to a Band of Hope in Brunswick Square, of which Mr. Willicott, who is now dead, was the head. My mother married again, and my stepfather, whose name was Collins, though good and religious, was not a fatherly person. I went into business in Regent Street, where I fell and lived with a Greek, who threw me over. I speak seven languages more or less well, and play four instruments, so you see my education was not neglected. Twelve years ago I lived in a fine house in Porchester Terrace, and now I live in the streets. My sister is very well off, and, I believe, lives in Park Lane, and has a country house at Staines. I am not certain of her addresses, however, as she has given me up altogether. The last time I saw her she came to Millbank Prison and paid two guineas for me. She said it was the last time, and it has been. I was given £15 on Saturday night, but I fooled it all away. I am continually being hunted out of my lodgings as soon as they hear I am Miss Fay and have been in prison. Sometimes when I look back and remember the days when I was spoken of at school as the prettiest and the cleverest girl, I look in the glass and see what I have become.” The piece concludes that subsequent inquiries in other quarters confirm the main facts in this pathetic story.

The Pall Mall Gazette, dated 27 October 1892, prints a very damning piece on Tottie, but at the same time raises ethical questions on the treatment of inebriates such as her. “That miserable specimen of humanity, Tottie Fay, who has haunted the metropolitan police courts for years, and who has been convicted of drunkenness hundreds of times, has at last been sent to penal servitude. Her latest offence was theft, and we call attention to the case now because it is typical of a class which calls loudly for exceptional treatment. Tottie Fay has long lost all moral control. No sooner has she been out of prison than she has been in again, and to send an offender like her to penal servitude now, in the hope of reclaiming her, is merely to put the country to useless expense. Compulsory detention in her case ought to have been enforced years ago, and then she might have had a chance. Sir Peter Edlin had no alternative yesterday, but is it not time that something was done in the way of an alteration in the law to meet the necessities of offenders of the Tottie Fay type?”

Following Tottie’s harsh sentence, Mr. JC Phillips, of Holloway, wrote to the Home Secretary asking him to reconsider the sentence. A letter from the Home Office stated that the Home Secretary had carefully considered the circumstances and he saw no reason for interfering with the sentence passed by the judge, as reported in both The Western Mail, dated 15 November 1892, and the Newcastle Weekly Courant, dated 19 November 1892.

Less than two months later, on 9 December 1892, Tottie was certified Insane and transferred to Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum in Crowthorne, Berkshire. I wonder what event inside Wormwood Scrubs triggered this certification. The public interest in Tottie Fay never wavered and her sad fate was widely reported throughout the country. The first report was in the Yorkshire Herald, dated 13 December 1892, which stated that “Tottie Fay has, after a careful investigation, been declared a lunatic. No one who has seen her disport herself in the dock can be under the delusion that she is in full possession of her senses.” I do not know how much of her sentence she actually served, since a physician would have been required to pronounce her fit for release. She would have been due for release sometime in late 1895.

An article in the Huddersfield Chronicle and West Yorkshire Advertiser, dated 19 February 1894, mentions her. Tottie Fay, once well-known in the London police courts, was said to be very violent, maniacal was the word used in the official document, and had to be removed from her room to a cell where there was no furniture to break nor glass to smash.

Six months later a rather different Tottie emerges from an article in the Westminster Budget, dated 24 August 1894, spoken by a Broadmoor staff member to a visitor. “Even prison could not quench Tottie Fay’s ruling passion which was for notoriety. She would often contrive to secrete all sorts of odds and ends in the way of bits of rags which she would somehow fashion into a sort of bustle which she would wear under her dress in order to make her look more stylish than the rest of the prisoners. On one occasion Tottie had actually found means to improve, from her point of view, her complexion, for she had somehow managed to get hold of some whitening and some brick-dust, with which she imparted to her face that deathly hue and curious red which paint and powder produce. But apart from this she was by no means a badly behaved girl, though to my mind it is better for her to be in prison and well looked after than out of it at the mercy of her own weak mind.”

Eight months later another interesting article appears in the Westminster Budget, dated 26 April 1895, titled “The Notorious Tottie Faye, Drunkenness as a Form of Insanity.” Dr Julius Price, who was a visitor of prisons and asylums, met Miss Fay on a visit to Broadmoor and notes – “Among the inmates, I found the notorious Tottie Fay, whose many visits to the police court have resulted in what should have been discovered many years ago, that she is a confirmed lunatic. Here, as was the case when she was at Wormwood Scrubs, her absorbing desire was for personal adornment. To this end she will go to any extreme, getting herself up with brick dust and chalk, when better means are not available. The lady gracefully presented me with the accompanying photo she had had taken of herself at her own expense by a local photographer (seen here) who had been allowed to attend the asylum, from which it is difficult to believe that the costume is made up entirely out of her asylum attire.” The article goes on to argue the case for State-controlled inebriate retreats rather than general prison since alcoholism was a disease not a crime.

An article in Reynolds’s Newspaper, dated 21 June 1896, mentions that Tottie Fay was an inmate at Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum in Friern Barnet, in the county of Middlesex. I have found only one official entry in the Lunacy Registers of Tottie entering and being released from Colney Hatch and that is later between 1899-1901.

Tottie is still making headlines in the newspapers. An article in Lloyd’s Weekly, dated 21 June 1896, and the one in Reynolds’s Newspaper mentioned above, both relate to a basket of clothes – frippery and faded finery of feminine attire – left at the booking-office of the Great Western Railway some three years ago. Tottie being incarcerated had been unable to return and collect her belongings. The St. Giles’ Board of Guardians did not want to pay the dues accruing on her possessions and made no application for them.

An article featuring Mr. Albert De Rutzen, a barrister of the Inner Temple and the sitting magistrate at Marylebone for fifteen years, Westminster for five years, now at Marlborough Street, appears in Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, dated 20 June 1897, and gives insight into how his hands were tied when sentencing Tottie. He is praised for being one of the most patient of men, listening to all that could be said for and against a prisoner. Every time Tottie Fay appeared before him at Marylebone Police Court he always expressed the opinion that the proper place for her was a lunatic asylum as a confirmed dipsomaniac, but he was obliged to administer the law as he found it, and in prison after all she would be kept away from temptation. The report confirms that Tottie is currently in an asylum but does not state which.

On 1 Oct 1897 Tottie was committed to Fisherton Asylum in Salisbury, Wiltshire.

After just under two years treatment at Fisherton Asylum, on 6 Sep 1899 Tottie was discharged ‘Not Improved’ to Colney Hatch Asylum in Friern Barnet, Middlesex.

At this asylum her treatment was more successful, and she was released after eighteen months on 18 March 1901. Her condition on release was ‘Relieved’ RELD in the record book. Relieved often meant sent to another asylum.

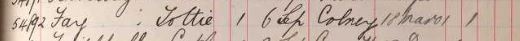

The Inebriates Act 1899, represents a legislative experiment for the reclamation of the habitual inebriate, who will now, in place of being fined or imprisoned, be detained for reformative treatment. The change in the law represents acceptance of medical opinion that inebriety is a form of disease which cannot be cured by punishment any more than insanity can. The change in the law is due to some extent to the notorious drunkenness of Tottie Fay and Jane Cakebread, both now dead.

North-Eastern Daily Gazette, 3 Jan 1899

It has taken the nation a long time to recognise the fact that the craving for strong drink is a disease to be medically treated, and not a criminal offence to be punished by imprisonment. The two women, now dead, known as Tottie Fay and Jane Cakebread, irreclaimable drunkards, largely helped forward this piece of beneficent legislation. As object lessons of the pitiable condition to which the human will is reduced by indulgence in strong drink, they did more to bring round the change of public opinion in the desired direction than the reams of essays issued by medical experts.

Newcastle Weekly Courant, 7 Jan 1899

Tottie you have gained immortality!

Tottie is next found on the Lunacy register admitted to Bristol Asylum on 18th March 1901, where she was to spend almost 2 years, discharged 22 Nov 1902, again RELD to Horton Asylum (below).

Tottie is first recorded entering Horton Asylum on 22 Nov 1902 and discharged on 2nd July 1903 ‘Relieved’. We cannot yet find where Tottie was relieved to as the Lunacy Patient Admission Registers available online are missing the records for 1903.

On 3 Jul 1907 Tottie was again committed to Horton Asylum as Patient #52292.

Nine months later Tottie died on 1 February 1908 in Horton Asylum at the age of 58 and was buried on 6 February 1908 in the Cemetery in Horton Lane in plot #75b.

| Admitted | Discharged | Asylum | Reason Discharged |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 Dec 1892 | 23 Oct 1895 | Broadmoor | “Unsound” |

| Online Records | Missing | for 1895/96 | TBC |

| 01 Oct 1897 | 06 Sep 1899 | Fisherton | Not-Improved |

| 06 Sep 1899 | 18 Mar 1901 | Colney Hatch | Rel’d |

| 18 Mar 1901 | 22 Nov 1902 | Bristol | Rel’d |

| 22 Nov 1902 | 02 July 1903 | Horton | Rel’d |

| Online Records | Missing | for 1903 | TBC |

| 03 July 1907 | 01 Feb 1908 | Horton | Died |

Finally, a fitting epitaph to Tottie Fay is a poem written by Punch and printed in the New York Tribune, dated 27 December 1903.

Honor To Whom Honor

‘Jane Cakebread’ and ‘Tottie Fay’ were both inebriates of the worst type… yet these two persons did more toward securing for us the act of 1898 than any others.”

Report of the Inspector under the Inebriates act.

When through the annals of the past, Posterity, you stray : When your judicial eye is cast On England of to-day, ‘Mid all our greatest, whose the name Ye most shall hasten to acclaim, Writ large upon the scroll of Fame ? – Jane Cakebread, Tottie Fay. Others have done their humble best The fiend of drink to slay : Sir Wilfred’s keen crusading zest Has had its little say ; C.-B. and honest John have tried To cure the ill which none denied, But what are such as these beside Jane Cakebread, Tottie Fay ? Great martyrs of a noble cause, Heroic parts ye play Who to reform your country’s laws Dared fling your lives away ! The cell, the van, the judgement hall, The terrors of the prison wall, Disease and death – ye dared them all, Jane Cakebread, Tottie Fay. Then let no other claimants boast That they have fought the fray Which ye alone have won – at most Mere armchair warriors they : Immortal twain! With tooth and claw And bloody scalp and broken jaw, Undaunted ye have braved the law, Jane Cakebread, Tottie Fay!