b. 1857 – d.1915 – A Victorian Murder Case

Intro

For a brief, but intense period, Mark Skull found himself an unwilling player in a classic Victorian murder case and endured having his family life and loss splashed across the newspapers in the UK and wider world. It was a personal tragedy that caused him great anguish and upheaval and led to the breakdown of his family unit and set him on the miserable path to his premature demise in Long Grove Hospital in the centre of the Epsom Cluster. Had the case been current it would be the subject of countless voyeuristic TV documentaries and reconstructions trampling over the human feelings and misery left in a violent tragedy’s wake.

Mark was born in 1857 to parents Charles and Jane in the rural Wiltshire village of Dauntsey, near Chippenham. Charles, like most of the residents of Dauntsey, derived his living from the land as a farm labourer. Mark would be shocked to revisit his home village today as the M4 motorway now cleaves it in two. He was one of at least five siblings and David, born 1854 was the closest in age to him. He was baptised in the village church on December 18, 1857.

The 1861 census picks the family up living at Turnpike Road, Dauntsey with Charles giving his occupation as an agricultural labourer, oldest son William a “farmer’s boy” and the rest of the children as scholars. Ten years on the Skulls are still on Turnpike Road. David and 14-year-old Mark have been promoted to agricultural labourer and farmer’s boy, respectively.

Seeking his fortune

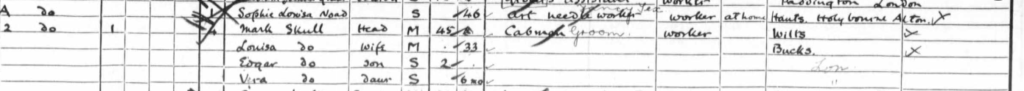

Some time between 1871 and 1881 Mark has decided to try his luck in London as many young country men and women did. Life in the country may have seemed idyllic for some but life was hard, the work often back breaking and the living conditions sometimes pitiful. The nineteenth century saw a mass emigration from the countryside to the industrial towns where work was rumoured to be plentiful and the standard of living higher. Mark is boarding in Chelsea in 1881 with a Clara Skull, his sister-in-law married to Mark’s brother George, and is working as a groom. In Victorian times a groom would typically be employed with a coachman and stable hand in looking after horses for a rich family of which there was no shortage in 1881 Chelsea.

Mark met Louisa Timblick, a Buckinghamshire servant girl seven years his junior. They married in Chelsea in 1884 where, curiously, Louisa’s name is given as Naomi. In 1887, back in Wiltshire, Mark’s brother David died at the young age of 33. His widow would have had a struggle to raise her family alone especially as she was pregnant at the time of David’s death and Mark and Louisa stepped in and agreed to take in their three-year-old daughter Mary Jane. They nicknamed the toddler Polly and she effectively became Mark and Louisa’s first child.

In 1891 the family are living at 34 Wellesley Terrace, Willesden. Mark is now calling himself a coachman, suggesting he has graduated from being a groom. The coachman would be steering the horse that pulled the coach of his employer. The likelihood is that he would now be responsible for a groom and a stableman. Mark and Louisa have registered “Polly” as their daughter, not niece, which reflects on how they now thought of her. The couple were devoted to the child and spent precious money on her music lessons.

By 1895 the Skulls are ensconced in 16, Fernhead Road, Paddington. It is a respectable street housing an assorted mix of tradespeople. Their neighbours include builders, plumbers, dentists, insurance salesmen and piano dealers. Their house would currently sell for three quarters of a million pounds. Francis Thompson, poet, lodged in Fernhead Road around Mark’s time and twenty years after Mark, the comedian Norman Wisdom was born and spent his early childhood in a room at number 91. Early in 1896 Louisa gave birth to their first surviving natural child – a little boy they name James Sidney but call him mainly by his middle name – and their family quartet seems a stable, happy and secure one. But, within a year, tragedy would strike, and nothing would ever be the same for any of them.

- SKULL, JAMES SIDNEY MARK

- Mother’s maiden name: TIMBRICK

- GRO Reference: 1896 M Quarter in PADDINGTON Volume 01A Page 32

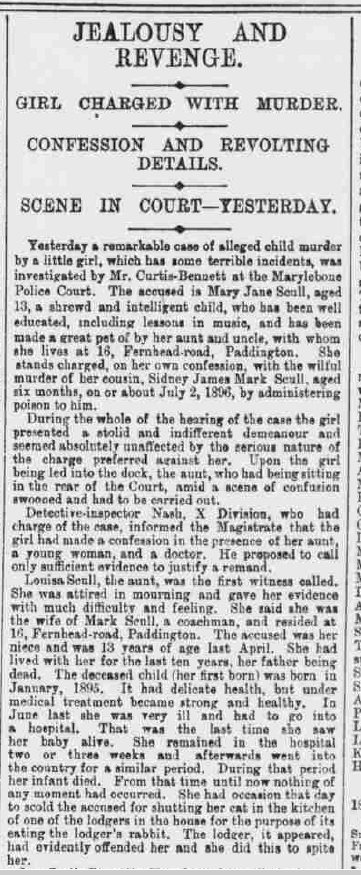

Murder Most Foul

Mary Jane, now 13, was resentful of the baby from the off. No longer was she the apple of her guardian’s eye and the hostility her stepdaughter showed baby Sidney perturbed Louisa. A couple of times she had to speak to her about it. In June of 1896 Louisa was ill with a tumour and was admitted to hospital for a few weeks and then went to the country for a couple more weeks, on medical advice, to build up her strength. While Louisa was hospitalised, baby Sidney fell ill and died. The doctor noted there was an epidemic of diarrhoea in the district and diagnosed that as the cause of death. At the time young children perishing from diarrhoea was not uncommon. Sidney had been a weak child since birth but had been growing in strength. Mark had the unenviable task of breaking the tragic news to his wife while she lay ill in hospital.

On her return to the family home Louisa had cause to admonish Mary over an incident where she had shut the cat in their lodger’s kitchen with the intention of encouraging the animal to eat the lodger’s rabbit. Somehow, the lodger had offended Mary. While Louisa scolded Mary Jane, the girl casually revealed:

“I done the baby.”

Louisa: “Done what?”

“I put poison in the baby’s bottle.”

Louisa: “What poison?”

“The poison I got for the toothache.”Asked her where she got it from, the girl replied:

Conversation Mary Jane and Louisa

“From Mr Linny’s.” [Mr Linny was the name of a chemist a few doors away.]

Louisa: “What did you do it for?” pleaded a distraught Louisa.

“Because you thought more of the baby than you did of me.”

Louisa: “Did you know you were going to do this before I went into the hospital?”

“Yes, I had made up my mind to do it.”

Louisa: “How much did you get?”

“Two penny-worth of camphorated chloroform, and I put the whole lot into the baby’s feeding bottle.”

The revelation was shocking. Especially because Mary Jane showed no remorse or emotion in recounting her act of murder. The police were informed.

The case was heard at Marylebone Police Court with Mr Henry Curtis-Bennett conducting the investigation. Poor Louisa was torn by the desire to see justice done for her dear baby son and the wish not to condemn Mary Jane to a life of imprisonment and punishment. She even pleaded with Mr Bennett to be allowed to continue to care for the girl. Mark Skull, on the other hand, wanted no more to do with his stepdaughter. He said he could not contemplate having her back.

“She has pretty much killed my missus and that’s not the first time,” he said, curiously. Mark Skull concluded by saying that Mary Jane was “dangerous and should be put away for a lifetime.”

Curtis-Bennett showing a great deal of empathy ruled that the case should not proceed any further and that Mary Jane be sent to a home. The Banbury Advertiser reveals that the home was in West London and the girl would be trained as a servant, a career she had expressed some liking for. Curtis-Bennett was later knighted and was famous for surviving a murder attempt by angry suffragettes.

The following is the text of an interview Louisa gave to Lloyds newspaper after the case was heard, note the name is spelt Scull with a ‘c’:

A representative of Lloyd’s paid a visit to 16 Fernhead Road, Paddington, and was enabled to interview Mrs Scull, although that lady is exceedingly ill in consequence of what has transpired. Mrs Scull, who is a pre-possessing young woman, evidently in very ill-health, says she has had her niece living with her since she was four-years old, she being now 14 years of age. From the first the child has always shown a peculiarly perverse and stubborn disposition, being very jealous and quick to resent punishment. If corrected for an offence she would find some means of annoying those who corrected her. She has been a source of great trouble to her uncle and aunt, who have done all they could to bring her up properly, and who, despite her disposition, have a great affection for her. Naturally quick, and usually well-behaved before strangers, they wished to take good care of her education, and so tried to give her a good schooling. Some of their first difficulties with her arising in consequence.

At the school she was sent to her jealous temperament soon became apparent, and for displaying her spite upon her companions she had to be removed from several institutions. Advised to put her to a boarding school, her guardians did so, sending her to one in the neighbourhood of Westbourne Park, where she was kept all day, being taken in the morning and fetched home at night. Here they had a great deal of trouble with her, she attempting to run away, as often as possible resenting by every means in her power the idea of restraint. The opinion of her aunt is that she is mentally deficient, having an unrestrainable temper and exhibiting a peculiar cunning in obtaining her ends. Some little time before the baby’s death her mother, who is living, though her father died soon after she went to live with Mrs Scull, came from the country upon a visit because of some tales sent her by Mary Jane. It was proposed that she should leave her aunt and uncle, but the child would not hear of it, threatening to give her mother the slip and run away if she attempted to take her. Knowing her peculiar disposition, the point of her going away was not further urged, to Mrs Scull’s poignant regret to-day. Mrs Scull has had several children, but none of them to live until the baby boy was born, with causing whose death little Mary Jane Scull is charged. The child was a beautiful little fellow of six months old when the fatal occurrence took place. His mother had never been able to nurse him, but he thrived wonderfully on his bottle, being fed on “humanised” milk. In consequence of Mrs Scull’s bad state of health, and the knowledge that she would have to enter a hospital to undergo a serious operation for tumour, a woman was employed to look after the baby, who, on the mother leaving home, was placed in her charge. Though never dreaming that Mary would hurt the baby, yet she had noticed how jealous she was of attention that had been paid to some other nieces.

Mrs Scull, before going to the hospital, told the baby’s nurse never to allow “Polly” to be, alone too long with him, and to keep his food in her entire charge. This was faithfully promised.

“I had only been in hospital a short time,” said the poor mother, “when my husband came to see me. I recollect. It was on a Thursday. and my first words to him were: “Oh, dear, how is it you have not brought baby to see me?'” He could not speak for a moment or two. and then he told me baby was gone. I felt as though I should die. My lovely boy, whom I had left in perfect health, to die so suddenly and without me seeing him. I couldn’t bear the thought of it, and the shock made me very ill, much worse than I should have been. A photograph was taken of him as he lay dead, and that is all I have to remind me of what he was.”

The photograph was seen by Lloyd’s representative, and is that of a remarkably fine baby. Continuing her story, Mrs Scull went on: “I had no suspicion of anything being wrong. There was an epidemic of diarrhœa at the time, and my poor baby was said by the doctor to have died of diarrhœa and convulsions. His sufferings were terrible. I have been told, and that is what makes my grief so bitter now.”

Asked as to the way in which the present discovery was made, Mrs Scull said, “Polly wished to annoy me because I was cross with her, and said to me, ‘I done baby.’ I said. ‘ What do you mean?’ She said again. ‘I done him. I put poison in his bottle.’ I was so shocked I fainted away, but on coming to questioned her further. She then told me what I told the magistrate, how she had put the toothache mixture in his milk. I said, ‘Whatever made you do it? Was he cross or troublesome?’ She said, ‘No, he was playing and laughing at the table when I gave it to him.’ I said. ‘Oh, Polly, what made you do it?’ and her reply was, ‘Because you cared for baby more than me.’ Then I fainted away again, and the doctor was sent for by somebody who saw how ill I was. It was while I was senseless he asked what had caused me to faint in such a way, and then Polly told him what she had told me. At night the police came when Polly was gone to bed: they said they must see her and take her to the doctor, and she got up and went with him. I do not think for a moment she thought of the consequences of her act or of her confession.”

Such is the story of this peculiarly pathetic case, as told by Mrs Scull, whose condition is most pitiful.

Lloyds newspaper interview with Mary Jane

Constance Kent similarities

The case was widely covered in the fervent popular press and threatened to become a Cause Célèbre in the way that the Constance Kent affair had just over 30 years earlier. Constance was the 16-year-old daughter of a wealthy widowed father who was convicted after confessing to killing her three-year-old stepbrother in, coincidentally, rural Wiltshire. Constance was sentenced to hang but this was commuted to life imprisonment and she did actually serve 20 years. She led a full life on her release never bothering the criminal system again and lived to be 100, dying in Australia in 1944. The case excited the media no end and has been the subject of much speculation and titillation ever since. Most recently Kate Summerscale’s best-selling book The Suspicions of Mr Whicher and a subsequent TV dramatisation captured the public imagination. The reason that Constance has attained such longevity in true crime history maybe lies in the public fascination with the class system. The Kents were a wealthy upper middle-class family replete with servants whilst the Skulls were working class people whose trials and tribulations were far less fascinating to the masses.

Sad aftermath

The Skulls endeavoured to put the trauma and tragedy behind them. A second son, Percy Edgar, was born to them in 1898 and a daughter followed in 1900. In the 1901 census the family have left the house that must have held much sorrow and where everyone knew who they were and what happened to them and are now resident at 2 Chichester Road in Paddington.

This area was more downmarket than Fernhead Road and considered a slum area. The road was eventually demolished to build the Westway and the Warwick Estate. In 1904 the family have moved to nearby Delamare Street.

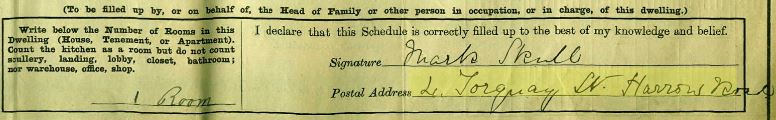

Something happened around this time because by 1907 Louisa has left Mark and is with a John Jaycock and has taken young Edgar and Vera with her. In 1911 John, Louisa, Edgar and Vera are living together in Taplow, Buckinghamshire. Louisa’s new partner is described as a handyman. Mark, however, is living alone at Torquay Street, Harrow Road. He is listed as a cabman.

Mark, it seems, has tried in life to better himself. Moving from the country to the town. Holding down employment, marrying and raising a family. He kindly took in his niece as his own to help her and his late brother’s family when death visited them. Perhaps he could never come to terms with his niece’s crime and the murder of his first baby boy? Maybe he held himself responsible? Who knows what mental strains dogged him in the years that followed? Losing his wife and his two young children must have been a fatal blow. At some point following us finding him alone in 1911 he must have broken down.

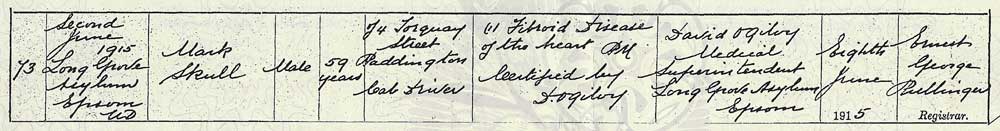

He died in Long Grove mental hospital at the age of 58 in 1915 and was buried in a pauper’s grave #1797a. Mark’s death certificate reveals he died from fibroid disease of the heart.

Louisa lived on to 1954 and their children Percy and Vera passed away in 1975 and 1974, respectively. The big question remains, though, – Whatever Happened To Mary Jane?

Redemption?

A newspaper article from Reynolds News throws more light on and raises more questions about the whole incident. Inspector Nash appraises the court that three years before the baby died, Mary Jane had attempted to poison the whole family by putting carbolic acid into their soup. As a result, the Skulls became seriously ill. No proceedings followed. How strange then that Louisa would beg for her return in court? Even stranger is the fact that Mr Curtis-Bennett and Mr Kirby, the court missionary, felt that Mary Jane was sufficiently low risk she be trained and placed as a servant in domestic service. Curtis-Bennett made it clear he did not think there was sufficient evidence beyond the girl’s confession for a murder charge to be brought but did he not think she had administered the poison or was he of the opinion that no poison was ever given?

Another curious fact is that Mary Jane is referred to in the court hearings as being aged 13 at the time of the crime but her birth and baptism records show she was actually 15. Was this a genuine vagueness about her age? Or was there a motive behind exaggerating her age downwards.

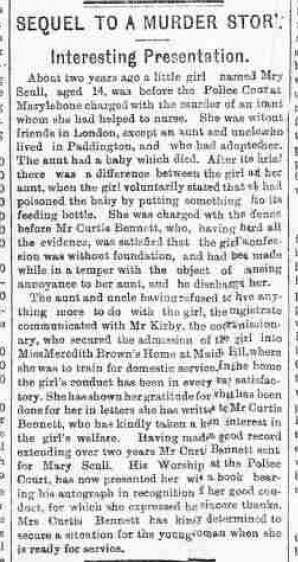

Two years later, in 1899, a further article in the South Wales Echo reveals more about Mary Jane. The article contends for the first time that Henry Curtis-Bennett believed that the girl’s confession was made in anger following a row with Louisa. It also discloses that Mary Jane had been placed in Miss Meredith Brown’s Home at Maida Vale. Meredith was one of the most famous social reformers of her time, noted for her book Only A Factory Girl. In 1908 Meredith Brown’s obituary in the Times described her thus: “A very remarkable woman, full of faith and of consequent zeal, in the noble cause of benefiting her poor and degraded sisters.”

Mary Jane’s progress in the home had been laudable, and she had written to Curtis-Bennett expressing her thanks for all he had done for her. In return he had presented her with a signed book and pledged to find her a position when ready for domestic service.

Author’s comment:

This is Mark Skull’s story, sadly his life is defined by the death of his first son and the sensational legal case that ensued. His mental health decline that ended in his demise in Long Grove Hospital in 1915 can surely be traced back to the tragic events of 1896, almost 20 years earlier.

It has transpired that Henry Curtis-Bennett, the police court chief and the court missionary Mr Kirby both felt strongly that Mary Jane did not commit murder, and both were sufficiently impressed by her that they expressly took an interest in her future. They did not feel it appropriate she should stay in the home of Mark and Louisa, despite their feeling she was innocent and Louisa’s desire to have her back home. Was there something about the relationship between Mark and his niece that unsettled them? Did they identify mitigating circumstances that were not aired in court?

If Mary Jane was unstable and murderous then her good luck mirrored Mark’s bad. She came up against two sympathetic, forward looking legal men who guided her into the care of one of the most prominent social reformers of her time. Her absence from public record after 1899 leads one to believe she led a productive and law-abiding life thereafter. Let us hope so.